Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

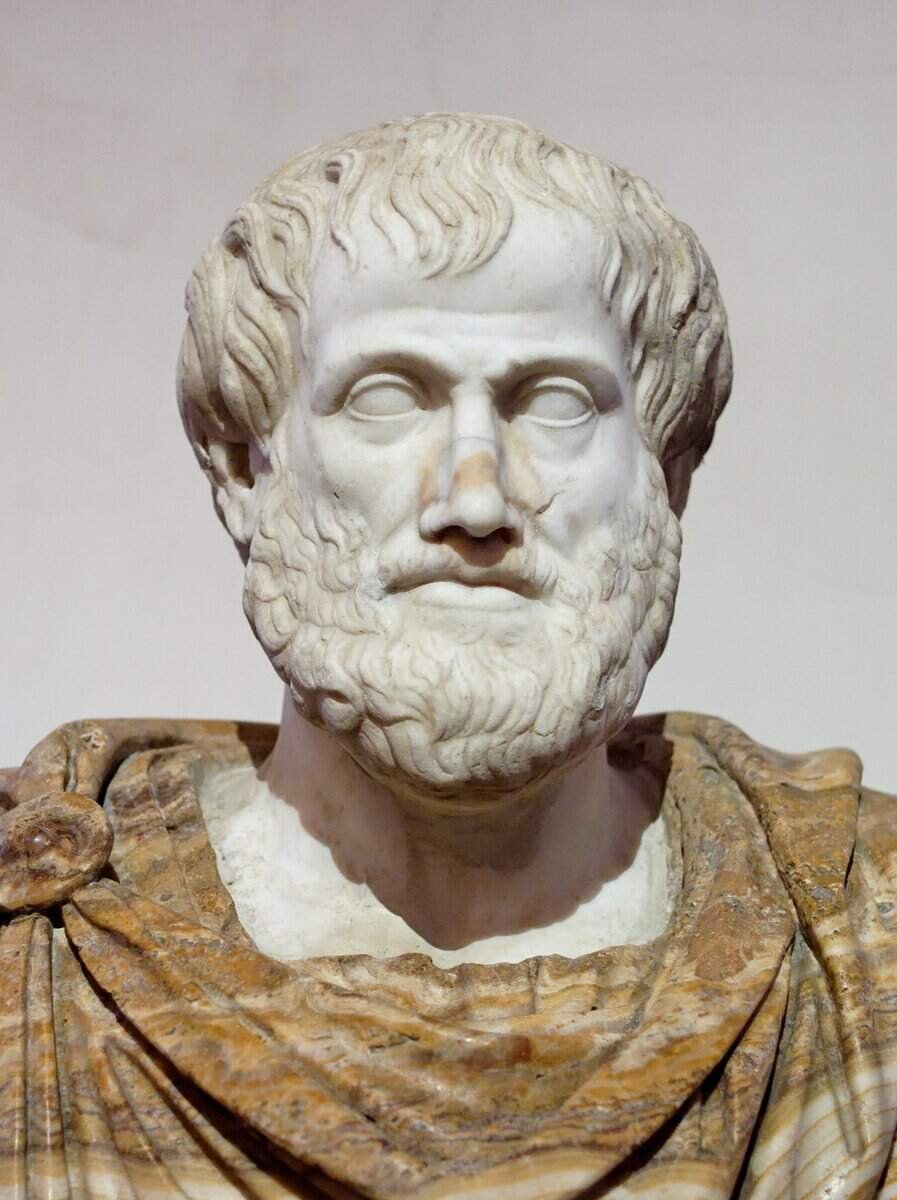

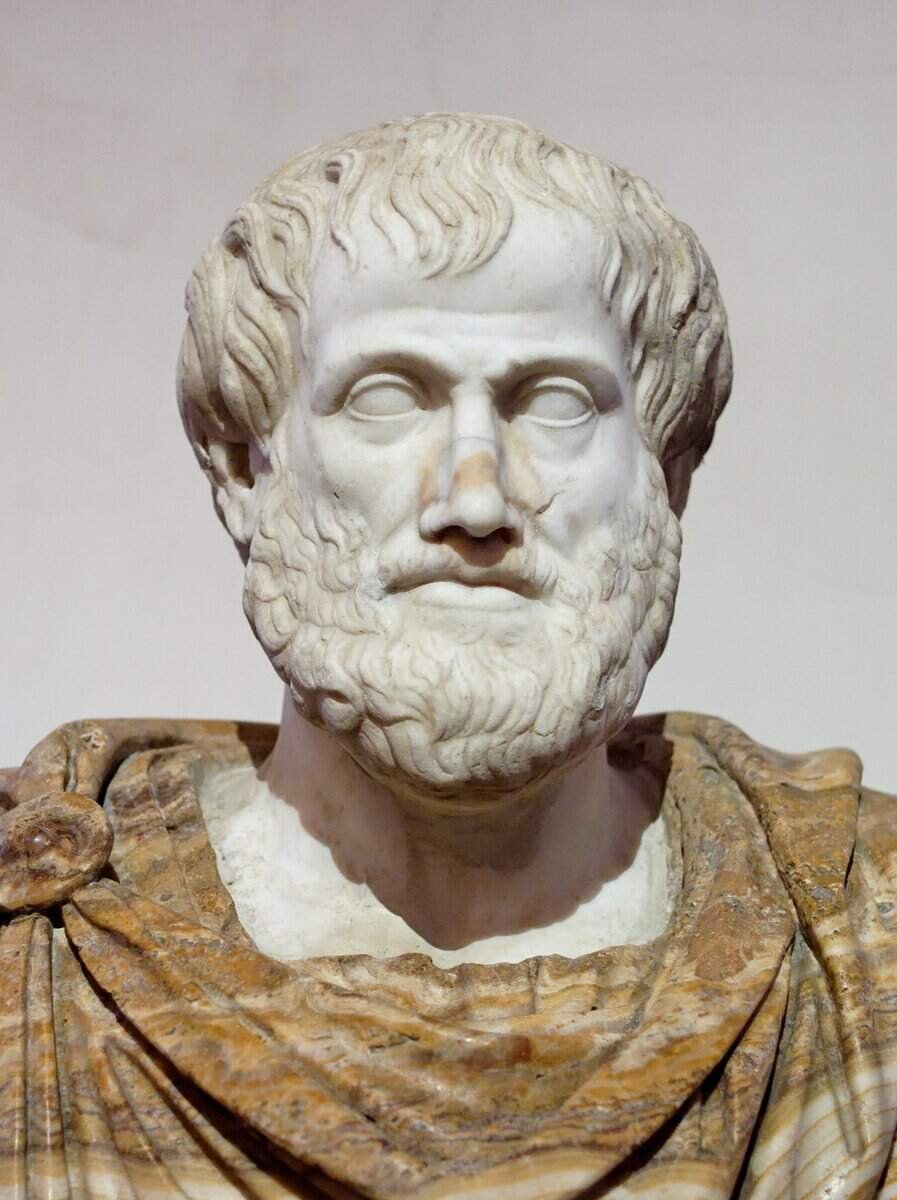

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

?Have you ever wondered how the rules you use when you argue, decide, or reason were first shaped into a system that could be taught and tested?

Imagine you’re sorting a stack of claims—emails, legal briefs, policy proposals—and you want a reliable way to tell which follow from which. Aristotle took that everyday task seriously, turning informal reasoning into a structured method you can learn and apply. In doing so he gave you tools that have guided Western thought for more than two millennia.

This article will show you what Aristotle did, why his system mattered then and matters now, and how his ideas compare with logical traditions in Asia. You’ll get close readings of core concepts, a map of historical influence, and practical notes on how Aristotelian logic still shapes reasoning in law, science, and even contemporary AI.

When Aristotle speaks of logic, he is primarily naming a toolkit for assessing arguments and discovering truth. You’ll find his system grounded in forms of argument (like syllogisms), classifications of propositions, and rules for valid inference. Logic is both descriptive—showing how reasoning actually proceeds—and normative—setting standards for good reasoning.

Aristotle’s collected writings on these topics are conventionally grouped as the Organon, a body of texts that treat categories, propositions, inference, scientific demonstration, and dialectical reasoning. In practical terms, the Organon gives you step-by-step ways to test whether one claim follows from others.

Aristotle worked in the intellectual shadow of Plato and within the broader currents of Greek inquiry. While Plato was mostly concerned with metaphysical forms and ideal knowledge, Aristotle turned his attention to concrete argumentation and the mechanics of thought. He wanted to know how you can move from premises to conclusions in a way that secures understanding.

The Organon emerged in an intellectual environment that prized debate, teaching, and the classification of knowledge. Aristotle’s aim was practical: provide reliable methods for teaching, scientific investigation, and persuasive reasoning. When you read his texts, you’re reading a project that wants to make reasoning teachable and testable.

Aristotle’s logical corpus gives you a sequence of tools. Each text serves a distinct function:

Each work gives you a layer of the system—from the vocabulary of thought to the mechanics of proof and the pitfalls to avoid.

At the core of Aristotelian logic is the syllogism. You use a syllogism when you connect two premises to arrive at a conclusion that necessarily follows. The classic example is:

Aristotle classified syllogisms according to figure and mood and proved which combinations produce valid conclusions. When you master his rules, you can test whether a given set of premises supports a conclusion with certainty—or whether the reasoning is defective.

Why does this matter for you? The syllogism teaches you to inspect the structure of arguments, not just their content. It makes clear the difference between persuasive rhetoric and demonstrative proof.

In the Posterior Analytics, Aristotle asks: what is scientific knowledge? For you, the answer matters when you want explanations, not just true beliefs. Demonstrative knowledge (episteme) arises from premises that are true, primary, known, and explanatory.

You’ll notice this is not merely an epistemic checklist. Aristotle insists that scientific understanding must show why something is the case via premises that are necessary and universal. When you demand explanations in science or policy, you’re echoing Aristotle’s requirement for demonstration.

Aristotle begins at the level of language and thought. In Categories he gives you a taxonomy for speaking about things—substance, quantity, quality, relation, place, time, position, state, action, and affection. This taxonomy helps you avoid category mistakes: the kind of confusion that occurs when you treat a property as if it were a substance.

For practical reasoning, you’ll use categories to frame hypotheses, classify evidence, and keep your concepts clear. The Categories also link language to ontology: how you talk reflects, and sometimes distorts, what is.

Not every context demands demonstrative proof. In politics, law, or everyday debate you often work with persuasive or probable premises. Aristotle’s Topics offers techniques for arguing from commonly held opinions, while On Sophistical Refutations teaches you to spot fallacies—wrong moves that may still seem persuasive.

If you’re constructing or evaluating public argument, Aristotle’s attention to dialectic gives you strategies for plausible reasoning and safeguards against rhetorical manipulation.

Once Aristotle’s works were transmitted into both the Islamic and Latin West, they became central to intellectual training. Thinkers such as Avicenna and Averroes commented extensively on Aristotle, and figures like Thomas Aquinas integrated Aristotelian logic into theological and philosophical frameworks. When you read medieval scholastic texts, you’ll see a persistent concern with syllogistic structure and demonstrative proof.

This long lineage matters because it made Aristotle’s method the default way of teaching rigorous thinking in universities for centuries. Your modern concept of “logic” owes a great deal to this institutional history.

When you compare Aristotle with Asian traditions, parallels and contrasts surface that clarify what is distinctive about his system and what is shared across cultures.

Both traditions put formal tools at the service of debate and epistemic justification, but they emphasize different priorities—Nyaya tends to institutionalize procedural rules for debate, while Buddhist logicians often link logic tightly with epistemology and soteriology.

Chinese intellectual history did not institutionalize formal logic to the same extent, but you will find logical thinking in Mohist writings, which treat argumentation and definitions in a technical way. Later Neo-Confucian and Daoist writings address reasoning indirectly through hermeneutics and metaphor, focusing on moral and contextual judgment rather than formal proof.

| Feature | Aristotelian Logic | Nyaya (Indian) | Buddhist (Dignāga/Dharmakīrti) | Mohist/Chinese |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core focus | Syllogistic inference; categories; demonstration | Inference in debate; pramāṇa theory; five-part syllogism | Perception and inference as epistemic means; propositional logic | Practical argumentation, definitions, analogical reasoning |

| Typical form | Three-term syllogism (deductive) | Five-member syllogism; emphasis on hetu (reason) | Two- or three-part inference forms; theory of signs | Practical claims; less formalized universal system |

| Epistemic aim | Scientific demonstration (episteme) | Justified belief and debate victory | Knowledge linked to liberation; rigorous epistemology | Moral and pragmatic reasoning |

| Notable concerns | Categories, necessity, universality | Valid sign; fallacies; debate norms | Valid inference; criterion of perception | Rhetoric, definitions, applied reasoning |

This table gives you a bird’s-eye view. It shows that while formal reasoning is global, traditions differ in structure, aims, and institutional embedding.

Aristotle’s system is powerful but not all-encompassing. A few limitations you should keep in mind:

Despite these limits, his method remains valuable for teaching clear thinking and for understanding how argumentation functions in many practical domains.

You’ll encounter Aristotelian logic in many unexpected places. Medieval scholastics used it to structure theological proof and to train disputants. Islamic philosophers engaged with and transformed Aristotelian ideas, sometimes producing innovations that later fed into Western thought.

In modernity, formal logic transformed the field: Boole and Frege recast logic into algebraic and symbolic terms. Frege explicitly aimed to remedy what he saw as the limitations of syllogistic logic, yet he built his innovations upon a conceptual awareness that Aristotelian logic had made discussion possible.

You can trace a direct line from the Organon to modern disciplines: law, where structured argument is central; science, where demonstration and hypothesis testing follow Aristotelian patterns; and cognitive science, where the study of reasoning often begins with the kinds of distinctions Aristotle made.

When you argue in a courtroom, design a research program, or structure a policy memo, Aristotle’s concerns will feel familiar. His teachings help you:

For people working in AI and computational reasoning, Aristotelian logic provides historical perspective and conceptual tools. While contemporary logic used in programming and machine learning is more often symbolic or probabilistic, the notion of specifying inference rules and checking validity is Aristotelian in spirit.

You won’t need to accept every metaphysical claim Aristotle made to use his method. Modern philosophers and educators reinterpret his insights in secular terms: syllogistic structures can be seen as templates for argument-checking, and the Posterior Analytics’ demand for explanatory depth matches contemporary calls for causal explanation in science.

You can adapt Aristotelian tools to modern debates—for example, using categories to clarify policy options or applying dialectical techniques to moderate online discussions. The normative thrust—insisting on clarity and justification—remains relevant.

Here are concrete practices you can adopt from Aristotle:

These habits help you move from intuition to accountable reasoning.

You now have a map of how Aristotle turned the scattered art of argument into a teachable, rigorous system. His syllogistic method, his concern for categories and demonstration, and his practical guides for dialectic gave you durable intellectual tools. Even when later logicians improved on his formal expressiveness, they were standing on a foundation Aristotle helped build.

When you reason, teach, or design systems that depend on clear inference, Aristotle offers more than antiquarian interest. He gives you a set of practices—make premises explicit, demand explanatory depth, and check structure before persuasion—that still sharpen thought. If you want to improve the quality of arguments in your organization, your classroom, or your public work, returning to Aristotle’s insights will give you principled, time-tested guidance.

If you’d like, you can comment with an argument you’re working on and I’ll help you test it using Aristotelian templates. Or, tell me which comparative tradition you’d like to examine more closely—Nyaya, Buddhist logic, or Chinese argumentation—and I’ll outline how their techniques might change how you reason.

Meta Fields

Meta Title: Aristotelian Logic: Birth, System, and Enduring Legacy Today

Meta Description: Learn how Aristotle formalized logic in the Organon, shaped Western thought, and how his syllogistic informs modern reasoning, science, and comparative philosophy.

Focus Keyword: Aristotelian logic

Search Intent Type: Informational / Comparative / Analytical