Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

Can ancient Taoist principles help you rethink sustainability in a world driven by metrics, markets, and technology?

You probably encounter sustainability conversations framed by numbers, policy targets, and ethical debates that often assume a Western philosophical backdrop. Yet, Eastern traditions such as Taoism offer a different vocabulary—one rooted in relationality, humility, and a non-coercive orientation toward life—that can reshape how you think about environmental responsibility. This article will give you conceptual tools drawn from Taoist thought and show how they can be made relevant, rigorous, and practical for modern ethics.

You will read about core Taoist concepts, canonical thinkers and texts, historical impacts on Chinese environmental practice, and a comparative account that places Taoism alongside Aristotle, Stoicism, and modern environmental philosophies. The aim is not to romanticize the past but to provide you with frameworks that can inform policy, corporate strategy, urban design, and everyday choices.

Taoism (sometimes spelled Daoism) originates in ancient China and offers a philosophical and religious response to how humans should be in the world. At its heart is a conception of the Tao (Dao), often translated as “the Way,” which names an underlying process or pattern that manifests in natural order and human affairs.

Taoist thought privileges attunement over domination. Instead of prescribing strict moral rules, it recommends practices and dispositions—such as non-coercive action, naturalness, and humility—that align a person with the flow of life. You will find that these ideas have immediate ethical implications for how you approach environmental problems, because they shift the moral focus from control and extraction to fit, restraint, and reciprocal flourishing.

The Tao names an ineffable source and pattern of change. Although the Dao is elusive to define, its ethical pull is clear: those who follow the Dao act in ways consonant with the larger order rather than opposing it. You can understand the Dao as a metaphysical and normative anchor for living in proportion to the world around you.

The classic Daoist text, the Dao De Jing (Tao Te Ching), attributed to Laozi (Lao Tzu), repeatedly emphasizes the limits of language in capturing the Dao. Still, it offers practical counsel: reduce force, value simplicity, and trust emergent harmonies.

Wu wei is often mistranslated as “inaction.” A better rendering is “non-forcing” or “effortless action”—acting in a way that does not artificially impose human will upon systems that have their own dynamics. For your environmental thinking, wu wei suggests interventions that work with ecological processes rather than override them.

That means preferring restoration techniques, regenerative agriculture, and adaptive management strategies that leverage natural capacities instead of rigid, one-off controls. Wu wei encourages you to ask whether a given intervention amplifies resilience or undermines it.

Ziran, commonly translated as “naturalness” or “spontaneity,” underscores an ethic of letting things be as they are when possible. This is not naive laissez-faire; rather, it’s an orientation that prizes context-sensitive actions that respect the integrity of ecosystems and species.

For sustainability, ziran invites you to build policies that are contextually informed, culturally sensitive, and ecologically congruent, avoiding universalist fixes that ignore local conditions.

Taoist metaphysics uses the yin-yang motif to emphasize complementarity, interdependence, and cyclical balance. Opposites are interwoven and transform into one another, reflecting the dynamic relationality of the world.

This relational lens has direct ethical consequences: it pushes you to think about feedback, trade-offs, and systemic effects rather than isolated metrics. Ayin-yang approach encourages you to attend to the quality of relationships among humans, nonhumans, and institutions.

If you want authoritative reference points, the Dao De Jing and the writings attributed to Zhuangzi (Chuang Tzu) are indispensable. These texts articulate the central metaphors, ethical stances, and practices of philosophical Taoism.

You will also encounter layers of later Taoist authors and religious movements who developed ritual, alchemical, and ecological practices. While the Dao De Jing and Zhuangzi lay the theoretical groundwork, later traditions operationalized Taoism in practices related to health, land management, and community life.

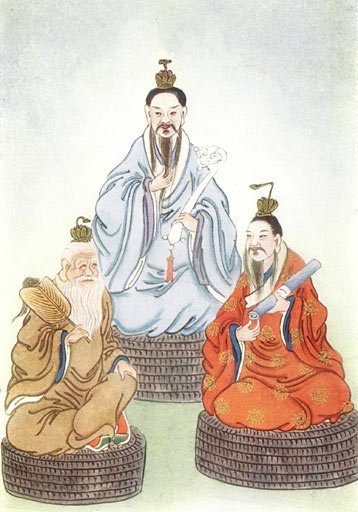

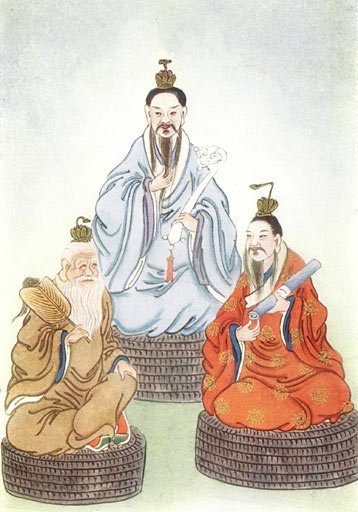

Laozi and Zhuangzi represent complementary emphases: the former tends toward concise aphorisms and political counsel, the latter toward allegory, irony, and thought experiments that unsettle fixed assumptions about the self and the world. Together they form a philosophically rich, practical orientation toward living with nature.

Taoist ethics differ from many Western frameworks in method and aim. Instead of offering prescriptive duties or maximizing aggregate welfare, Taoism focuses on cultivating dispositions that harmonize you with the emergent order of life. This yields a non-anthropocentric, process-oriented ethics.

You are invited to judge actions by their capacity to preserve or restore balance rather than by abstract principles alone. Moral value, on this account, depends on how deeds foster resilience, relational health, and the flourishing of diverse life forms.

Taoism resists straightforward human-centered moral calculations. Trees, rivers, mountains, and animals are not mere resources but participants in a living whole. That perspective aligns with modern ecocentric approaches that attribute intrinsic worth to ecosystems and species.

By decentering human exceptionalism, Taoist ethics make room for policies that prioritize long-term integrity over short-term human convenience. You might find this perspective useful for arguing in favor of conservation measures that have no immediate economic payoff.

Taoist moral imagination privileges humility and simplicity. Laozi repeatedly warns against pride, excess, and ostentation. A humble stance, ethically, means limiting your claims on nature and accepting constraints that serve broader ecological health.

These virtues translate into sustainability practices such as lowering consumption, designing for longevity, and prioritizing low-impact technologies. Simplicity here is strategic: it reduces brittle dependencies and enhances resilience.

You can see Taoist sensibilities reflected in Chinese landscape painting, garden design, and traditional agricultural practices that emphasize harmony with topography and seasonal rhythms. Ideas originating in Taoist thinking shaped the cultural norms that favored land stewardship in ways distinct from Western land appropriation narratives.

Mountain worship, sacred groves, and local stewardship practices historically protected certain landscapes. While such protections were not uniformly applied or immune to exploitation, they illustrate how cultural conceptions of nature can materially affect environmental outcomes.

Taoist practices also influenced medicinal and herbal knowledge, emphasizing local biodiversity and sustainable harvesting. These historical connections remind you that ethical orientations matter; they shape institutions and behaviors over time.

How does Taoism compare to Western philosophical traditions that inform environmental ethics? You will find both convergences and tensions that are instructive for constructing a pluralistic, global environmental ethic.

Aristotle’s virtue ethics emphasizes character and teleology—living according to one’s nature and cultivating virtues. This has affinities with Taoist emphasis on dispositions and flourishing. However, Aristotle’s anthropocentric focus on human flourishing as the telos differs from Taoist non-anthropocentrism.

The Stoics emphasized living according to nature and accepting limits, which resonates with Taoist restraint. Yet Stoicism often privileges rational self-mastery and moral duty, while Taoism privileges spontaneity and contextual responsiveness.

Christian medieval thinkers like Thomas Aquinas offered stewardship frameworks that locate moral responsibility in the concept of caretaking under a divinely ordained order. That stewardship model can be combined with Taoist humility to produce a stewardship that is less domineering and more relational.

Modern environmental philosophies—utilitarianism, rights-based approaches, Aldo Leopold’s land ethic, and Arne Naess’s deep ecology—each bring resources. Leopold’s idea of enlarging the community of moral concern parallels Taoist relationality. Naess’s emphasis on intrinsic value and simpler living lines up with Taoist simplicity. Utilitarian cost-benefit methods often clash with Taoist suspicions of instrumentalizing nature.

Table: Comparative Snapshot of Ethical Approaches

| Dimension | Taoism | Aristotelian Virtue Ethics | Christian Stewardship | Deep Ecology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moral Center | Relational harmony (non-anthropocentric) | Human flourishing (anthropocentric) | Human duty to care under God (theocentric) | Intrinsic value for biosphere (ecocentric) |

| Key Virtues | Humility, simplicity, wu wei | Courage, temperance, prudence | Charity, stewardship, responsibility | Respect for life, simplicity, biospheric egalitarianism |

| Policy Implication | Contextual, adaptive, low-interference interventions | Education for virtues, moderate policies | Stewardship mandates, care responsibilities | Radical reductions in human footprints |

| Approach to Technology | Cautious, context-sensitive | Instrumental, assessed by virtues | Conditional, moderated by stewardship | Critical, often skeptical |

This quick comparison clarifies that Taoism contributes a distinctly relational and process-oriented toolkit that can complement rather than replace Western frameworks.

You will need guidance on translation from principle to policy. Taoist ethics can inform concrete choices in governance, business, urban design, and everyday life. The following sections show how to operationalize Taoist ideas without lapsing into mysticism.

When you design environmental policy with a Taoist tilt, prioritize adaptive governance, subsidiarity, and humility in decision-making. That means implementing iterative policies with monitoring and feedback loops, decentralizing authority to local ecologies, and being willing to reverse or modify interventions as systems respond.

You should favor policy instruments that enhance natural capacities—such as payments for ecosystem services that support restoration, incentives for regenerative agriculture, and zoning that preserves ecological corridors. Avoid rigid, technocratic mandates that ignore local variability.

For businesses, Taoist-inspired sustainability centers on incremental alignment with ecological processes. You can apply principles of circularity, material minimalism, and design for durability. Wu wei suggests interventions that reduce friction rather than imposing complex controls—think lightweight designs, biomimetic production methods, and supply chains that match the regenerative capacities of ecosystems.

Corporate governance can adopt humility by embracing transparency, internalizing ecological costs, and setting long-term incentives for managers that align with resilience metrics rather than quarterly earnings alone.

Urban planners informed by Taoist thought will privilege green infrastructure, permeable surfaces, and designs that adapt to local hydrology and microclimates. Instead of relying on rigid containment—channelizing rivers or importing water at scale—cities can use living systems (wetlands, green roofs, urban forests) to regulate climate and water cycles.

You should prioritize mixed-use neighborhoods and distributed energy systems that mimic the distributed, resilient patterns found in ecosystems. Such designs reflect ziran by working with rather than against local conditions.

Regenerative agriculture, agroforestry, and low-till methods align well with Taoist principles. You can design systems that rely on biological cycles, reduce chemical inputs, and build soil health. Wu wei shows up in practices that support natural pest control and nutrient cycling rather than heavy-handed eradication.

Land-use policy can incorporate sacred groves and community-managed forests that mimic traditional Taoist protections, combining cultural recognition with conservation outcomes.

You can translate Taoist ethics into everyday choices: consume less, prioritize locally produced goods, cultivate practices of care and attention, and support institutions that model humility and reciprocity. Mindfulness, slow living, and learning to recognize the limits of control are practical habits with ethical significance.

Small behavior shifts—repairing instead of replacing, choosing durable goods, planting biodiverse gardens—aggregate into meaningful systemic effects when supported by policy and culture.

No philosophical framework is without limits. You should be aware of critiques that say Taoist principles are vague, non-actionable at scale, or potentially conducive to passivity. Some worry that a Taoist orientation could legitimize inaction in the face of urgent crises.

These concerns are legitimate but not decisive. Taoism’s stress on attunement does not preclude decisive action; instead, it prescribes actions that are timely, context-sensitive, and designed to sustain system health. The key is to pair Taoist dispositions with robust institutional tools—scientific monitoring, democratic accountability, and ethical deliberation—that prevent passivity from turning into neglect.

Another critique concerns cultural translation: applying Taoism outside its East Asian context risks superficial appropriation or misinterpretation. You should approach integration respectfully, acknowledging historical particularities and collaborating with cultural practitioners where possible.

Finally, scale poses a challenge. Large-scale problems like climate change require coordinated, often disruptive interventions. You can reconcile Taoist ethics with large-scale mobilization by focusing on adaptive, phased strategies that align with natural systems and human communities rather than imposing one-size-fits-all technological fixes.

To make Taoism work for modern sustainability, you can adopt three integrative moves. First, combine Taoist dispositions (humility, simplicity, wu wei) with scientific knowledge and systems thinking, creating a hybrid ethic that is both wise and operational. Second, institutionalize Taoist principles via adaptive governance structures that reward restraint and resilience. Third, cultivate civic cultures that value long-term stewardship over short-term extraction.

You should also consider reconciling Taoist relationality with justice concerns. Environmental sustainability without social justice risks perpetuating inequalities. Therefore, a modern Taoist ethic must incorporate equity: protecting vulnerable communities, honoring indigenous knowledge, and redistributing burdens fairly.

By integrating Taoist sensibilities with scientific rigor and social justice commitments, you can craft a sustainability ethic that is ethically deep and practically effective.

Taoism offers you a philosophical toolkit that reframes environmental ethics around relationality, humility, and adaptive action. Its core concepts—Tao, wu wei, ziran, and yin-yang—encourage you to design interventions that respect the autonomy and dynamics of natural systems. When paired with modern science, democratic governance, and a commitment to equity, Taoist perspectives can strengthen policies, business strategies, and personal practices aimed at long-term resilience.

You are invited to test these ideas in your own contexts: try applying wu wei to a project by favoring minimal, reversible design choices; support policies that decentralize decision-making to local ecological communities; or cultivate personal habits of simplicity that reduce systemic strain. If you have insights, objections, or local examples of Taoist-inspired sustainability in action, share them—your practical experiences help refine how ancient wisdom can responsibly inform modern ethics.

Meta Fields

Meta Title: Taoism and Environmental Sustainability — Harmony for Modern Ethics

Meta Description: Learn how Taoist principles like wu wei, ziran, and relational ethics can inform modern sustainability in policy, business, and daily life.

Focus Keyword: Taoism and environmental sustainability

Search Intent Type: Informational / Comparative / Practical