Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

Have you ever found yourself questioning whether “truth” is something you can point to, or whether it’s more like a shifting pattern that you learn to read?

You may already know postmodernism as an academic label, an artistic mood, or a critique lobbed in public debates. At its heart, postmodernism asks uncomfortable questions about how claims to truth are produced, authorized, and sustained. That makes it simultaneously useful and unnerving: useful because it sharpens your skepticism about taken-for-granted assumptions, unnerving because it shows how many of those assumptions rest on social, linguistic, and institutional scaffolding.

In this article you’ll get a clear, practical account of what postmodernism means for truth, how major thinkers shaped the movement, and how Eastern traditions provide useful counterpoints. My aim is to give you conceptual tools you can use when facing contested claims—whether in policy, media, scholarship, or everyday conversation—without leaving you stranded in cynicism.

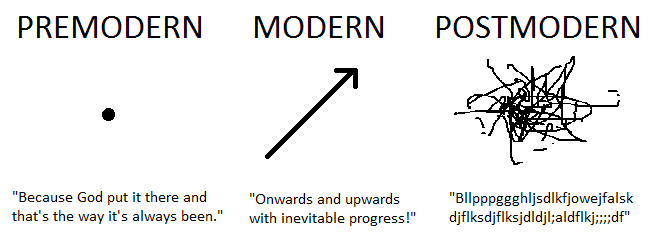

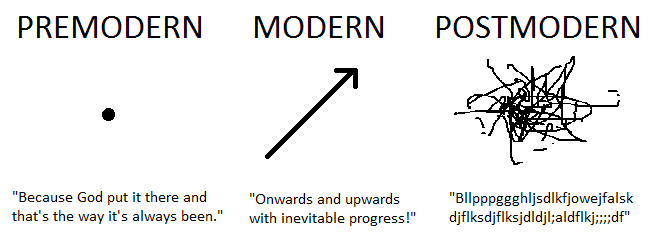

You can think of postmodernism as a family of attitudes and methods that emerged in the mid-20th century, reacting against certain promises of the modern era—progress, universal reason, stable subjectivity, and the idea that science alone can settle the most important questions. The term covers intellectual currents in philosophy, art, architecture, literary theory, and social thought.

Historically, postmodernism arises in dialogue with modernism and its heirs. Whereas modernism tended to trust grand theories and linear narratives of progress, postmodern theorists challenged those meta-narratives and foregrounded contingency, plurality, and discontinuity. That shift didn’t happen overnight; it reflects influences from Nietzsche and Heidegger, and later thinkers like Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Jean-François Lyotard, and Richard Rorty who reframed the stakes of truth and meaning in new ways.

Deconstruction, associated with Jacques Derrida, is often misunderstood as mere relativism. In practice, deconstruction is a method for reading texts and situations so you can reveal internal tensions, assumptions, and unstated hierarchies. Derrida introduced concepts like différance to show that meaning is generated in difference and postponed through chains of signification; meaning never lands as a final, context-independent object.

When you apply deconstructive reading to so-called factual claims, you examine the language, categories, and institutional practices that sustain those claims. You ask which terms are privileged, what binary oppositions are at work, and what histories or power relations are suppressed. That doesn’t mean you will end up saying “anything goes”; rather, you gain a finer sense of why certain claims have authority and where they might be vulnerable to reinterpretation.

Michel Foucault complements this perspective by focusing on power-knowledge: how institutions, discourses, and practices produce particular regimes of truth. For Foucault, truth is less a mirror of an external reality and more a product of arrangements—legal systems, medical frameworks, bureaucratic protocols—that decide what gets said and who can say it credibly. This turns your attention from abstract epistemology to concrete practices of verification and exclusion.

Jean-François Lyotard famously described postmodernity as “incredulity toward meta-narratives.” That skepticism urges you to treat grand claims—about history, progress, or universal human values—with caution, and to attend more closely to local, language-specific, and interest-laden forms of justification.

You don’t need to memorize a canon to engage with postmodern questions, but knowing a few landmark figures helps you grasp the conversation:

Friedrich Nietzsche: Not postmodern in the historical sense, but a crucial precursor. Nietzsche critiqued truth as a human construction rooted in will and metaphor. His genealogical method anticipates later skepticism about foundational claims.

Martin Heidegger: Reoriented philosophy toward questions of being and language, influencing later thinkers who worried that metaphysics concealed assumptions about subjectivity and truth.

Jacques Derrida: Developed deconstruction and wrote “Of Grammatology,” arguing that writing and textuality shape how meaning is produced. For you, Derrida asks you to attend to how language frames truth.

Michel Foucault: Wrote about how institutions shape knowledge (e.g., “Discipline and Punish”), showing the connection between power and the definition of truth. You should think in terms of practices, not just propositions.

Jean-François Lyotard: Diagnosed the loss of faith in meta-narratives in “The Postmodern Condition.” His work encourages you to value smaller, vernacular, and pragmatic forms of legitimacy.

Richard Rorty: Moved the conversation toward pragmatism, suggesting that truth can be treated as a utility for solidarity rather than as a strict mirror of reality. Rorty’s view is useful if you want to preserve action and democratic deliberation.

While these figures are central in Western postmodernism, comparing them with Eastern traditions enriches your perspective and helps avoid mistakenly treating postmodernism as purely negative or destructive.

When you compare Western postmodern skepticism with Eastern philosophical traditions, you find both differences and resonances. Eastern traditions often approach truth as practical, relational, or soteriological (concerned with liberation), which offers a different angle than Western metaphysical debates.

| Dimension | Classical Western (Aristotelian/Aquinas) | Postmodern Western | Eastern (Confucian, Daoist, Buddhist) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic claim about truth | Correspondence or coherence; truth as objective property | Contested, situated, language-mediated | Practical, relational, or pragmatic; sometimes transcending propositions |

| Relationship to language | Instrumental or representational | Constitutive; language shapes truth | Language is provisional; direct experience or praxis valued |

| Role of universals | Central (essences, natural law) | Suspicious of universals (meta-narratives) | Varies: Confucian norms, Daoist fluidity, Buddhist negation of inherent essences |

| Epistemic goal | Knowledge, certainty | Critique of foundations, pluralism | Ethical cultivation, liberation, harmony |

| Response to power | Less central | Power-knowledge analysis (Foucault) | Social roles and ritual (Confucius); non-attachment to constructs (Buddha) |

You can see parallels: Nagarjuna’s Madhyamaka critiques inherent existence in a way that resonates with deconstruction’s refusal of fixed essences. Daoist skepticism about rigid categories echoes postmodern interest in fluidity and multiplicity. Confucian thought emphasizes moral cultivation and the social production of obligations, reminding you that truth often functions within practices and relationships.

These comparisons help you recognize that skepticism about fixed truth is not unique to late-20th-century Western thought; it’s part of broader human responses to complexity. Eastern perspectives can also give you a constructive toolkit—disciplines for self-cultivation, attention to context, and pragmatic tests of what “works” in communal life.

You’ll find the effects of postmodern thinking across culture. In literature and art, postmodernism loosened narrative authority, foregrounded pastiche, and celebrated self-referentiality. In architecture and design, it rejected modernist purity for plural styles and irony.

In academia, postmodernism reshaped humanities and social sciences. Cultural studies, feminist theory, queer theory, and critical race theory all drew on insights about language, power, and marginal narratives to interrogate established canons. That brought important visibility to previously suppressed voices, but also sparked debates about standards of scholarship and truth.

Politically and socially, postmodern approaches have both empowered and complicated public discourse. On one hand, highlighting the contingency of dominant narratives has amplified marginalized perspectives and demanded institutional reform. On the other hand, critics argue that a radical skepticism about truth can be weaponized to erode shared facts and accountability. You need to keep both dynamics in view: postmodern critique can be liberating or destabilizing depending on how it’s practiced.

You’ll often hear the charge that postmodernism leads to relativism or nihilism—”all truths are equally valid”—but that is a caricature. Many postmodern thinkers were careful to avoid such flattening. Still, the concern has weight: if every claim is a product of power and language, how do you adjudicate between competing claims about, say, public health policy?

Critics such as Jürgen Habermas argued that postmodern skepticism can undermine rational-critical discourse and democratic deliberation. Others worry that rejecting standards of truth enables bad-faith actors to manipulate facts.

Defenders respond in several ways:

Methodological humility: Postmodernism trains you to be cautious about certainty and to attend to power; that can strengthen, not weaken, democratic reason by forcing better argumentation and transparency.

Pragmatic grounding: Thinkers like Rorty propose treating truth as a tool for social solidarity. For you, truth then becomes less about metaphysical correspondence and more about what helps communities flourish.

Ethical sensitivity: Feminist and postcolonial theorists adapted postmodern methods to highlight injustice and uplift marginalized ways of knowing. This shows that critique can be allied to ethical aims rather than nihilism.

To navigate these tensions, you can adopt a middle path: accept that many claims are situated and contingent, while insisting on standards of evidence, intersubjective norms, and institutional checks that allow for shared decision-making.

You live in a media environment where contested truth is a daily reality. Social media accelerates narratives, amplifies partial truths, and often rewards emotional resonance more than careful argument. Postmodern insights help you diagnose why some claims stick: narratives tap into identity, aesthetics, and institutional sentiments.

In technology and AI, questions about truth are urgent. Language models and algorithmic systems produce plausible statements without human-style grounding. Postmodernism prompts you to ask: Which truths are being encoded, whose data shapes the model, and what institutional power gets reproduced? That makes you better equipped to press for transparency, auditability, and multidisciplinary oversight.

In law and policy, postmodern awareness encourages you to scrutinize how categories—race, gender, disability—are constructed and enacted in institutional practices. That scrutiny can spur reforms that recognize complexity and protect rights while insisting on procedural standards.

In organizations and leadership, you can use postmodern sensitivity to better handle plural viewpoints. Rather than pretending to a single “objective” strategy that ignores cultural differences, your decisions can embrace multiple evidentiary modes—qualitative narratives, quantitative metrics, and ethical commitments—to produce more resilient outcomes.

You shouldn’t let skepticism become paralysis. Here are concrete habits you can adopt to be both critical and constructive:

Triangulate claims: When faced with a contested fact, consult diverse sources—empirical studies, first-person narratives, institutional records—to see where they converge and why they diverge.

Ask about provenance: Who produced the claim? What incentives, funding, or institutional pressures might have shaped it? Tracing provenance helps you identify biases without condemning all knowledge production.

Attend to practice: Evaluate claims by their consequences in practice. Does adopting a claim improve collective outcomes or only serve narrow interests? Practical testing is a common ground for adjudication.

Practice reflective equilibrium: Weigh your background beliefs, considered judgments, and theoretical principles, and adjust them to achieve coherence. This method helps you bridge particular claims and broader values.

Foster epistemic humility: Admit uncertainty publicly when appropriate. A culture that tolerates provisional knowledge better adapts to new evidence and reduces dogmatic clashes.

Build cross-disciplinary teams: Complexity often requires multiple lenses. Legal, scientific, historical, and ethical perspectives together yield stronger judgments than any single discipline.

If postmodernism dismantles simplistic grounds for truth, what constructive frameworks can you use? Consider pluralist epistemology: truth claims are assessed by multiple, interlocking standards—empirical adequacy, coherence with other well-established claims, pragmatic fruitfulness, and ethical legitimacy.

This pluralist stance is not a surrender to relativism. Instead, it recognizes that different domains call for different standards—scientific claims need reproducibility; moral claims need justification through reasons and consequences; historical claims need archival and testimonial corroboration. You can hold these standards simultaneously, using the right tool for the task while remaining open to revision.

Integrating Eastern practices enriches this approach. For instance, you might complement analytic scrutiny with contemplative practices drawn from Buddhist traditions to cultivate attention and reduce cognitive bias. Or you might borrow Confucian emphases on ritual and role to better understand how social practices sustain knowledge claims in communities.

To make this concrete, imagine you’re responsible for communicating a public health campaign. Postmodern skepticism alerts you to potential challenges: mistrust of institutions, competing narratives, culturally specific beliefs. You can act on that insight.

Don’t only assert statistics. Combine data with narratives that reflect people’s lived experiences.

Be transparent about uncertainties. Explain what is known, what is tentative, and what is being monitored.

Attend to institutional trust. Collaborate with community leaders whose credibility matters locally.

Monitor discourse practices. Track how misinformation spreads and address the underlying social anxieties rather than simply repeating corrections.

Using a postmodern-informed approach makes your communication more robust, because you engage with the social dynamics that determine whether a claim will be taken seriously.

When you question established truths, you also gain responsibility. Deconstruction and skepticism can be used to dismantle injustice, but they can also be weaponized to erode accountability. That means you should pair critique with constructive commitments.

Ethical intellectual practice requires you to:

Clarify aims: Are you critiquing to reveal oppressive structures, or merely to unsettle authority for its own sake?

Seek reparative outcomes: When a critique reveals harms, propose plausible alternatives or support remediation.

Preserve dialogic space: Encourage reasoned exchange rather than rhetorical foreclosure.

In short, your deconstructive tools should serve civic and ethical ends, not mere contrarianism.

Postmodernism changes the way you think about truth without offering a nihilistic escape route. It teaches you to be suspicious of absolute foundations, to attend to language and power, and to value plurality. At the same time, it invites you to act responsibly: triangulate evidence, cultivate humility, and aim for practical outcomes that sustain collective life.

You can use postmodern techniques to expose hidden assumptions and also to rebuild procedures that allow disagreement to be negotiated. That combination—rigorous critique plus constructive rebuilding—is what makes postmodernism a mature resource for anyone grappling with contested truths in the 21st century.

If this has prompted questions or if you have a concrete situation where disputing claims of truth matters—policy debates, corporate strategy, classroom discussions—share it. Reflecting on real cases helps turn theoretical clarity into practical skill.

Meta Fields