Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

?Have you ever wondered whether the perfect circle or the ideal justice you imagine exists somewhere beyond the objects you touch?

Imagine you’re holding a ceramic cup that’s slightly chipped. That cup makes you think of “cupness” — the idea that lets you recognize other cups despite differences. Plato argued that the thing you recognize, the perfect “cupness,” is not simply an abstraction in your mind but participates in a higher, more real realm of Forms. In this article you’ll examine why that claim matters, how it shaped Western thought, and how it compares to insights from Eastern traditions.

You’ll get clear definitions, historical context, and practical implications. This isn’t just a history lesson: you’ll see how Plato’s Theory of Forms speaks to ethics, knowledge, science, and even debates about AI and mathematics today.

Plato’s Theory of Forms (or Ideas) says that non-material abstract Forms are the truest reality, and the material world is a set of imperfect copies or instances of those Forms. You encounter particular things — trees, chairs, acts of justice — but these particulars are intelligible only because they resemble or participate in their respective Forms: the Form of Tree, Chair, Justice.

Plato presents this theory across dialogues such as the Republic, Phaedo, Symposium, and Timaeus. In the Republic he uses myths and metaphors — especially the Allegory of the Cave — to show how most people mistake shadows for reality and how philosophical education turns the soul toward the light of the Forms.

You should note that Plato’s language is often metaphorical. He doesn’t give a single systematic ontology; instead he builds a persuasive network of images and arguments across dialogues.

Plato formulated the Theory of Forms to address several philosophical problems that you probably still wrestle with.

If you notice multiple tables and say they’re all “tables,” what makes them all share the same table-ness? For Plato, positing a Form explains how distinct tokens instantiate the same property without collapsing them into mere names.

Material things change and decay, yet you still think of stable essences (like triangle or beauty). Forms supply a stable ground for those enduring concepts.

If you want objective standards for ethics and knowledge, Plato offers Forms — especially the Form of the Good — as the ultimate standard for truth, beauty, and justice. That gives a foundation for moral objectivity and rational knowledge beyond subjective taste.

You’re likely familiar with the Allegory of the Cave. Prisoners see shadows on a wall and mistake those shadows for reality. When a prisoner escapes and sees the sun, he recognizes the higher reality that produces the shadows. Plato’s point is pedagogical: philosophy releases the soul from illusion so it can apprehend Forms.

The allegory also ties epistemology and ethics: understanding the Form of the Good empowers just action. For Plato, virtuous political leadership requires knowledge of Forms, which is why philosopher-rulers are central in the Republic.

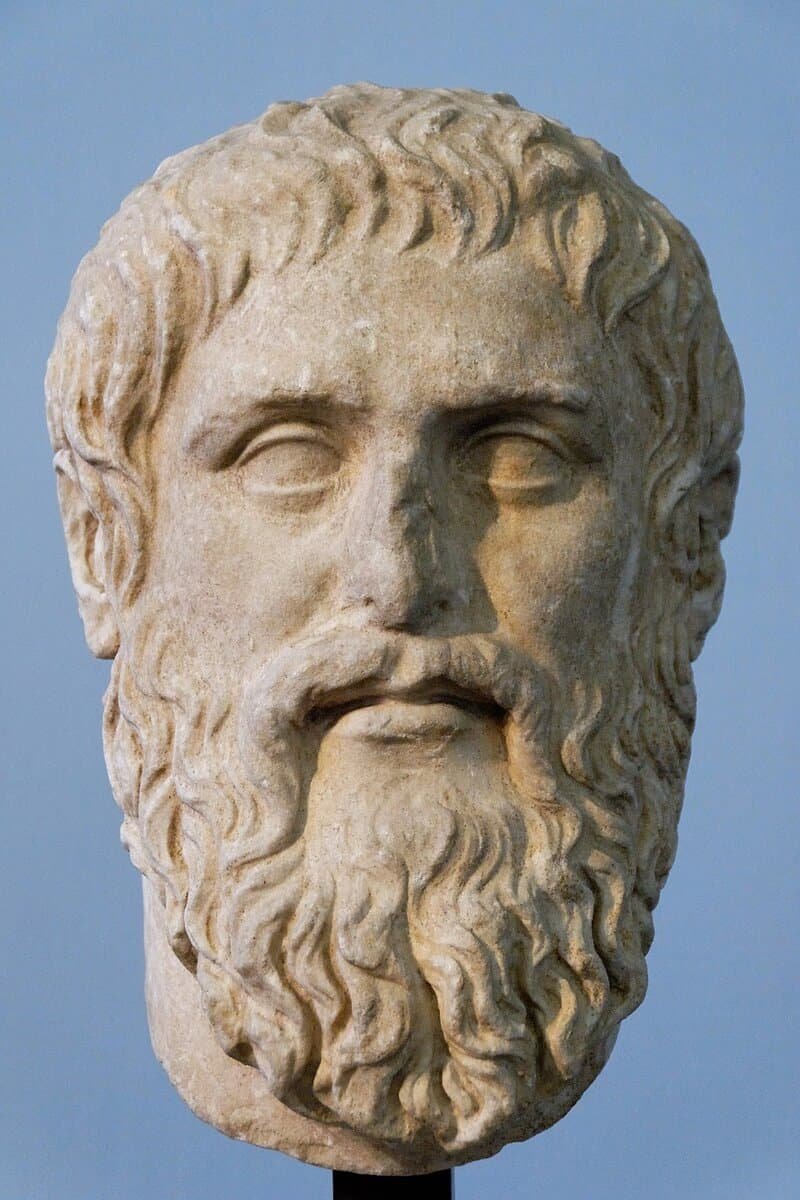

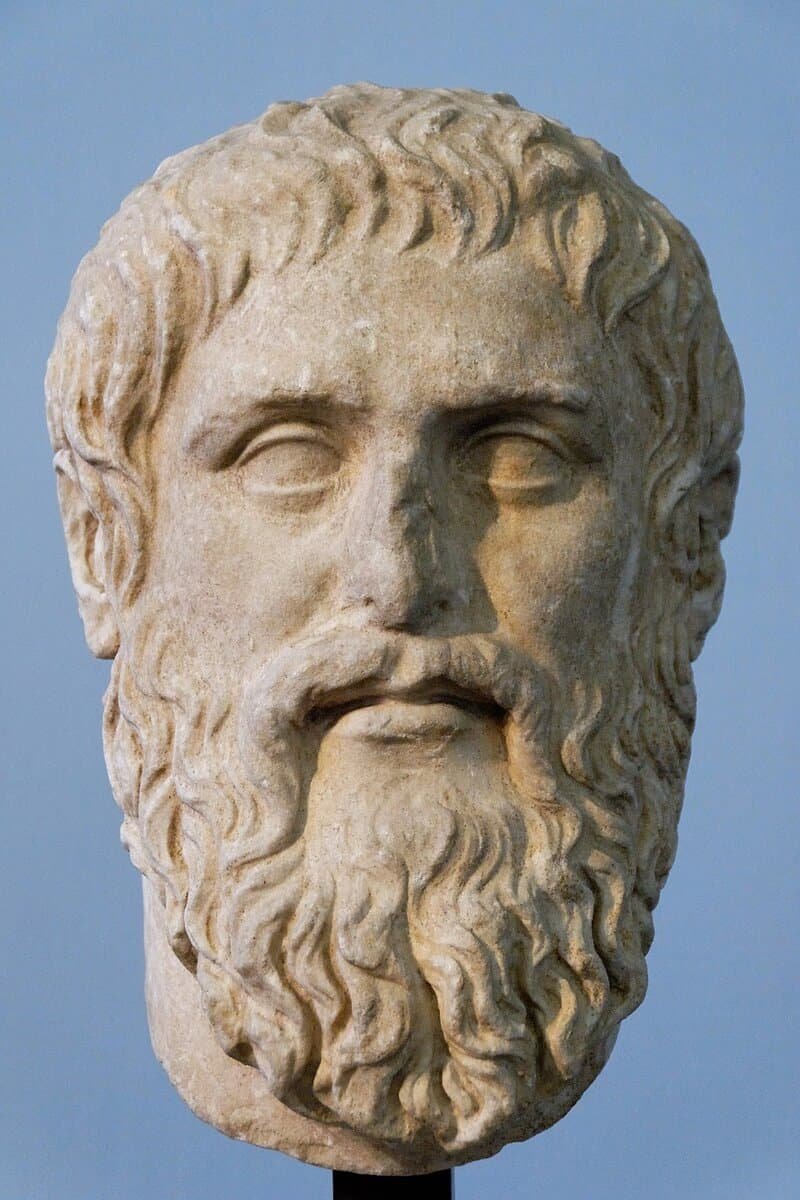

Plato himself (Athenian philosopher, student of Socrates) is the originator of the Theory of Forms. You’ll want to read the Republic for the most extended treatment; Phaedo concerns the soul’s immortality and the Forms; Timaeus offers a cosmological sketch connecting Forms to the crafted material world.

Aristotle, Plato’s student, critiqued Forms for positing separate entities and developed a hylomorphic account (form and matter as inseparable principles). Augustine and Plotinus adapted Platonic ideas into later Neoplatonism, spiritualizing the Forms in Christian metaphysics. Medieval scholastics (Aquinas, for instance) integrated elements of Platonic and Aristotelian thought into theological frameworks.

You should also note modern echoes: mathematical Platonism treats mathematical objects as timeless, mind-independent entities — a stance that owes much to Plato’s intuitions.

Plato anticipates and addresses several objections, though critics have responded across centuries.

If a Form unites many men, does that imply a third Form that unites the men and the Form? This regress was raised by Aristotle and remains a puzzle. Plato might respond by distinguishing levels of participation and by insisting Forms are not merely large particulars but ontologically different kinds of beings.

How does an immaterial Form relate to a material object? Plato uses the concept of participation rather than mechanical interaction: particulars instantiate or partake in Forms without a causal contact in the physical sense. Critics find this explanation obscure, and later Neoplatonists developed metaphors (emanation, hypostases) to make relations clearer.

Philosophers like the early modern empiricists (Hume, Locke) denied innate ideas and insisted knowledge arises from experience. Plato’s claim that the soul recollects Forms (anamnesis) is at odds with strict empiricism. You’ll see later defenses of abstraction that bridge some gaps, but the tension remains central to epistemology.

You should know how Aristotle departs from Plato because this split shapes much of Western metaphysics.

| Issue | Plato | Aristotle |

|---|---|---|

| Relation of Forms to particulars | Forms exist separately, beyond particulars | Forms (forms of things) are immanent in particulars (form-matter composite) |

| Change and permanence | True permanence resides in Forms | Change explained via formal and efficient causes working in matter |

| Epistemology | Knowledge is recollection of Forms; intellect apprehends eternal realities | Knowledge arises from abstraction from sense experience |

| Ethics | Objective Good exists as a Form; philosopher-knowers access it | Ethics grounded in human function and virtues developed in life |

This table should help you see why later medieval and modern thinkers favor one or the other: your metaphysical commitments about universals inform your approach to science, ethics, and mind.

You’ll gain insight by comparing Plato with Eastern traditions. The goal is not to equate systems but to spotlight useful resonances and contrasts.

These comparisons help you see that many traditions grapple with the appearance-reality divide, but they do so with distinct metaphysical and moral emphases.

If you accept Plato’s account, moral truths aren’t contingent or purely subjective; they’re anchored in the Forms. That gives normative authority strong objectivity: justice is not merely conventional but participates in the Form of Justice.

You’ll then ask: how do you access ethical knowledge? Plato’s answer is philosophical education and dialectic — refining concepts to perceive Forms more clearly. This has practical implications:

Modern readers adapt these ideas by prioritizing moral expertise and deliberative institutions, rather than absolute philosopher-rulers.

You’ll encounter Platonic intuition in debates about mathematics: are numbers discovered or invented? If you’re a Platonist, numbers and mathematical objects exist independently of human minds. That explains why mathematical truths seem necessary and universally applicable.

In science, the idea of underlying laws or structures (e.g., symmetries, conservation laws) function like modern equivalents of Forms: they are the invariant patterns that make phenomena intelligible. Scientists often treat laws as objective regularities, though whether they are Platonic entities or models remains contested.

Contemporary philosophy continues to wrestle with Platonic ideas in revised forms.

Philosophers of science sometimes endorse structural realism, claiming scientific theories capture the structure of the world rather than its intrinsic nature. This is congenial to a Platonic view where structures (Forms) are more real than accidental features.

Mathematical Platonists (e.g., Gödel’s sympathizers) maintain that mathematical entities are real and discoverable. Critics worry about epistemic access: how can you know non-spatiotemporal entities?

Nominalists deny universal entities, treating general terms as names or linguistic conveniences. Conceptualists locate universals in the mind. You should understand these positions because they offer naturalistic alternatives to Plato while attempting to preserve explanatory power concerning classification and knowledge.

Contemporary cognitive science examines whether categories and concepts are innate or learned. Plato’s idea of recollection is often reimagined as predispositions, cognitive architectures, or evolved conceptual scaffolding. You’ll see attempts to reconcile innate concept structures with empirical learning.

You’ll find it helpful to apply simple analogies to the abstract idea of Forms.

Consider an architect’s blueprint (Form) and a house (particular). The blueprint provides the essential pattern; many houses can be built from it with variations. The blueprint, however, is not a house — it’s a plan. Plato’s Forms function like blueprints for intelligible reality.

Think of the Form as an interface or abstract class in software that defines the behavior of objects. Specific objects implement the interface with concrete code. The interface determines what counts as a valid implementation; particulars are varied implementations.

These analogies aren’t perfect, but they show how a higher-level, invariant structure can ground many diverse instances.

You’ll see Platonic influence in systems that prioritize expertise, moral formation, and hierarchical models of knowledge.

You don’t have to accept Plato wholesale. You can adopt useful elements and revise others.

Accept:

Revise or reject:

| Dimension | Platonic tendency | Aristotelian tendency | Eastern tendency (general) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultimate reality | Transcendent Forms | Immanent forms in matter | Varies: Brahman (monism), Dao (process), Emptiness (Buddhism) |

| Role of senses | Deceptive, secondary | Important for abstraction | Mixed: senses are sources but also bound by illusion/attachment |

| Ethics | Objective Forms (Good) | Function-based virtues | Relational, duty-based (Confucian), non-dual (Vedanta), middle-path (Buddhism) |

| Knowledge method | Dialectic, recollection | Observation + abstraction | Meditation, moral cultivation, scriptural study |

This table gives you a heuristic for cross-cultural comparison without oversimplifying complex traditions.

Plato forces you to ask foundational questions: What is real? How do you know? What grounds ethical norms? Those questions remain central to science, law, education, and personal reflection. Even if you reject metaphysical Platonism, Plato’s dialectic trains you to test assumptions and seek deeper principles.

You’ll find Plato’s influence in contemporary debates about truth in a post-truth era: if you lose confidence in objective standards, public discourse becomes untethered. Plato’s insistence on rigorous inquiry serves as an antidote to intellectual relativism.

Consider how Plato’s theory might inform contemporary problems you care about:

These applications show Plato’s continuing relevance beyond academic philosophy.

Plato’s Theory of Forms invites you to consider that reality may have a structure beyond immediate appearances. Whether you accept that structure as transcendent Forms, immanent patterns, or useful metaphors, the theory challenges you to scrutinize how you classify, judge, and know.

You can take away three things: (1) the concept of Forms helps explain universals and the stability of concepts; (2) Plato’s arguments shaped centuries of metaphysical and ethical thought, and his legacy persists in many modern debates; (3) you can adapt Platonic insights to contemporary problems while revising elements that clash with empirical science and democratic values.

If this raises more questions for you — about mathematics, consciousness, or political design — consider reading Plato’s Republic and Phaedo alongside critical responses from Aristotle and later commentators. Reflect on how your commitments about reality influence the way you live, reason, and participate in public life.

Meta Title: Plato’s Theory of Forms: Beyond the Material World, Explained

Meta Description: A clear, comparative guide to Plato’s Theory of Forms — its origins, critiques, Eastern parallels, and modern relevance for ethics, science, and politics.

Focus Keyword: Plato’s Theory of Forms

Search Intent Type: Informational / Comparative