Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

? What responsibility do you owe to future generations, non-human life, and distant strangers when the climate is changing under your feet?

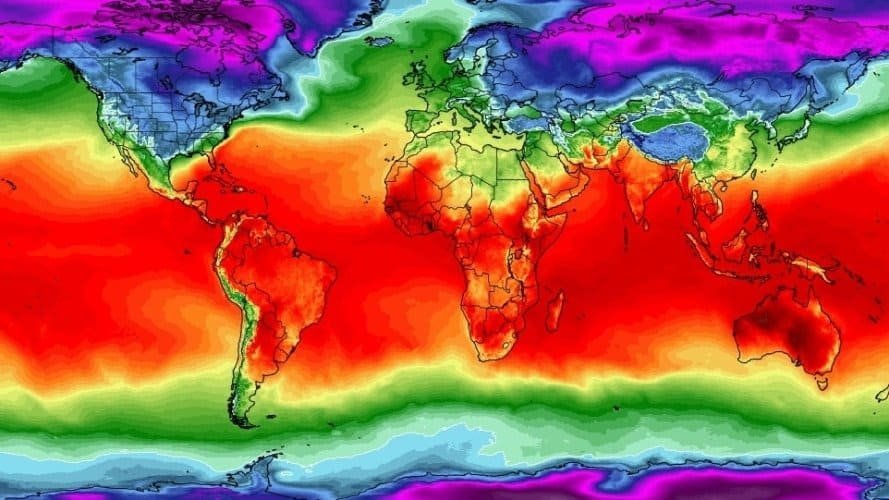

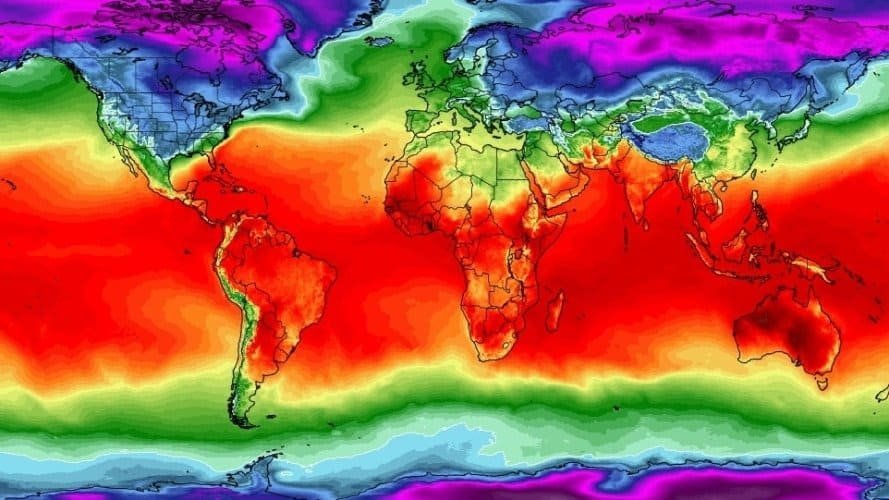

You live in an era when a single metric — atmospheric carbon concentration — tells a story about choices made across continents, industries, and lifetimes. Recent concentrations have crossed thresholds that climate scientists tell us are linked to more extreme weather, sea-level rise, and biodiversity loss. Those facts alone make climate change urgent, but you should also see it as a moral problem: it asks not only what you can do, but what you ought to do.

This article treats climate change as a moral imperative within global ethics. You’ll find a careful, comparative conversation between major philosophical traditions from East and West, an account of the conceptual resources each tradition offers, and practical implications for policy, institutions, and personal conduct. The aim is to give you intellectual tools and ethical clarity so you can assess obligations, prioritise action, and argue for systemic change.

When you call something a moral imperative, you claim that action is not merely prudential, strategic, or aesthetic: it is required by ethical reasons. A moral imperative carries normative force — that is, it binds agents who accept its premises. In the context of climate change, that force might arise from duties, rights, virtues, relational responsibilities, or the demands of justice that span space and time.

Two clarifications are important. First, moral imperatives come in different flavors: categorical commands (you must act regardless of consequences), prima facie obligations (you must act unless overridden), and pro tanto reasons (they weigh in the moral calculus). Second, the scope of moral concern matters. Do you owe duties only to compatriots, to all humans, or to non-human beings and ecosystems? How you answer will shape the nature and strength of the imperative.

Climate change forces a rethinking of standard ethical categories in three ways:

Because of these features, traditional frameworks — deontology, utilitarianism, virtue ethics — must be applied and sometimes revised. You should expect a blended ethical response: duties, consequences, character, and relational responsibilities all matter.

Understanding climate ethics benefits from tracing how different philosophical traditions ground moral obligation.

You can point to several influential Western sources:

These traditions are resourceful, but they often presuppose a human-centered moral community. The challenge is to extend concern beyond immediate human subjects and to accommodate intergenerational justice.

Eastern philosophies offer complementary insights that expand moral imagination:

These traditions emphasize relationality, humility, and long-term custodianship. They enrich Western frameworks by widening the circle of moral concern.

You’ll encounter several dominant ethical arguments in contemporary climate ethics. Each gives you a different reason to treat climate change as morally pressing.

If people have rights to life, health, and subsistence, climate harms that infringe those rights create duties to prevent them. Rising seas that displace communities, heatwaves that increase mortality, and loss of food security all implicate basic human rights. From this perspective, mitigation and adaptation are obligations to protect fundamental rights.

You should be attentive to the asymmetry between historical responsibility and current vulnerability. Industrialized nations contributed disproportionately to cumulative emissions, while many low-income countries bear the brunt of climate impacts. Climate justice demands reparative policies: differentiated responsibilities, loss-and-damage funding, and fair transition strategies that do not burden the least advantaged.

You weigh consequences and see that unchecked climate change produces vast, avoidable suffering. Minimizing aggregate harm demands urgent emission cuts and investment in adaptation. Cost-benefit calculations, when they include non-market values and future persons, typically favor significant mitigation.

Moral character matters. You should cultivate virtues such as temperance (restraint in consumption), prudence (careful deliberation about long-term risks), and solidarity. Climate action becomes a practice of cultivating virtues that sustain communal flourishing.

You have obligations to future persons who will exist if conditions allow. Climate harms compromise their ability to flourish. Principles of fairness, such as some versions of contractualism or reciprocity, imply constraints on present actions that impose heavy costs on those yet to be born.

You don’t have to choose East or West; you can integrate strengths from both.

Table: Comparative features of select ethical traditions and their contributions to climate ethics

| Tradition | Normative Focus | Contribution to Climate Ethics |

|---|---|---|

| Kantian deontology | Duty, universalizability, respect for persons | Grounds prohibition of practices causing foreseeable harm to others; supports rights-based claims |

| Utilitarianism | Consequential welfare maximization | Argues for strong mitigation to minimize aggregate suffering across time |

| Aristotelian virtue ethics | Character, flourishing | Encourages cultivated habits (temperance, prudence) aligning with sustainable living |

| Confucianism | Relational duties, ritual, social harmony | Promotes stewardship, role-responsibility, community-based sustainability |

| Daoism | Harmony with nature, humility | Supports non-extractive attitudes and long-term ecological balance |

| Buddhism | Interdependence, compassion, non-harm | Justifies ethical restraint and compassion for all beings, including future ones |

Ethical ideas have practical consequences. You can trace environmental movements and policy debates to moral convictions.

Ethical vocabulary — rights, justice, duty, stewardship — shapes legal frameworks, funding priorities, and public narratives. When you argue for strong climate policy, moral language is not decorative; it translates values into instruments like emission targets, compensatory funds, and legal protections.

Once you accept climate change as a moral imperative, policy direction follows.

You should advocate for policies that reflect both justice and efficacy: ambitious mitigation targets, equitable carbon pricing, phase-outs of fossil fuel subsidies, and investments in clean infrastructure. Ethically sensitive policy design includes transitional supports for affected workers and communities.

You’re part of a global order where richer nations have obligations to finance mitigation and adaptation in poorer countries. Moral reasoning supports mechanisms such as technology transfer, concessional finance, and loss-and-damage funds to address historical inequities.

Firms have duties not only to shareholders but to broader stakeholders. Corporate governance should internalize climate risks, disclose emissions, and adopt net-zero pathways. You can push for fiduciary duties that include long-term climate liabilities.

Courts and legal systems increasingly recognize climate harms as rights infringements. Strategic litigation by citizens and communities can force better compliance with emission targets and compel states to honor their duties. You should see legal action as one lever among many.

You may feel overwhelmed by the scale of the problem, but moral agency is manifest at multiple levels. Your choices matter in five ways:

Remember that ethical force often comes from coordinated action. The moral imperative supports both personal restraint and systemic transformation.

You’ll hear resistance grounded in common arguments. Here are focused responses.

Individual actions are necessary but not sufficient. The moral point is twofold: (1) individuals have duties not to contribute knowingly to harm and (2) collective change often begins with many individuals creating political and market pressure. Your actions can have multiplier effects.

Philosophers have long debated this, but many practical ethical views — contractualist, utilitarian, and virtue-based — provide reasons to protect future wellbeing. Parental responsibility and legal precedents for trusteeship also support precautionary duties.

Justice requires balancing development needs with climate limits. Ethical policy supports green development pathways, technology transfer, and concessional financing so you don’t pit rights to development against rights to a livable climate.

Ethical decision-making under uncertainty often favors precaution, especially when potential harms are catastrophic and irreversible. Reasonable risk management supports mitigation and resilience investments.

You can find resources in canonical texts when you read them for ecological sensibility.

These reinterpretations are not forced; they are respectful recoveries that show how enduring moral concepts can address new problems.

Given the complexity of climate harms, you should adopt a pluralist ethical approach:

This synthesis helps you avoid single-theory blind spots and creates robust justifications for comprehensive climate action.

You should be aware of unresolved ethical issues:

Philosophical work must continue alongside empirical research and civic experimentation to answer these questions.

You now have several reasons to treat climate change as a moral imperative. Whether you start from duties, consequences, virtues, or relational obligations, the ethical arguments converge on a demanding conclusion: action is required across personal, institutional, and political domains. Moral reasoning enriches scientific and economic arguments by framing climate change as a failure of justice, stewardship, and compassion.

Acting ethically means combining immediate mitigation with long-term institutional reforms and a commitment to fairness for those most affected. You don’t need to master every philosophical nuance to act; recognizing the moral stakes is already a decisive step. If you feel motivated, reflect on where your agency is strongest — vote, advocate, shift institutional norms, cultivate restraint — and commit to actions with both moral clarity and practical effectiveness.

If you’d like, comment on which philosophical argument resonates most with you, or propose a dilemma you face in aligning values with action. Your reflection helps shape the communal moral conversation that climate change urgently requires.

Meta Fields

Meta Title: Climate Change: A Moral Imperative in Global Ethics Now

Meta Description: An in-depth comparative analysis arguing that climate change is a moral imperative, drawing on Eastern and Western ethical traditions and practical implications.

Focus Keyword: climate change moral imperative

Search Intent Type: Comparative