Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

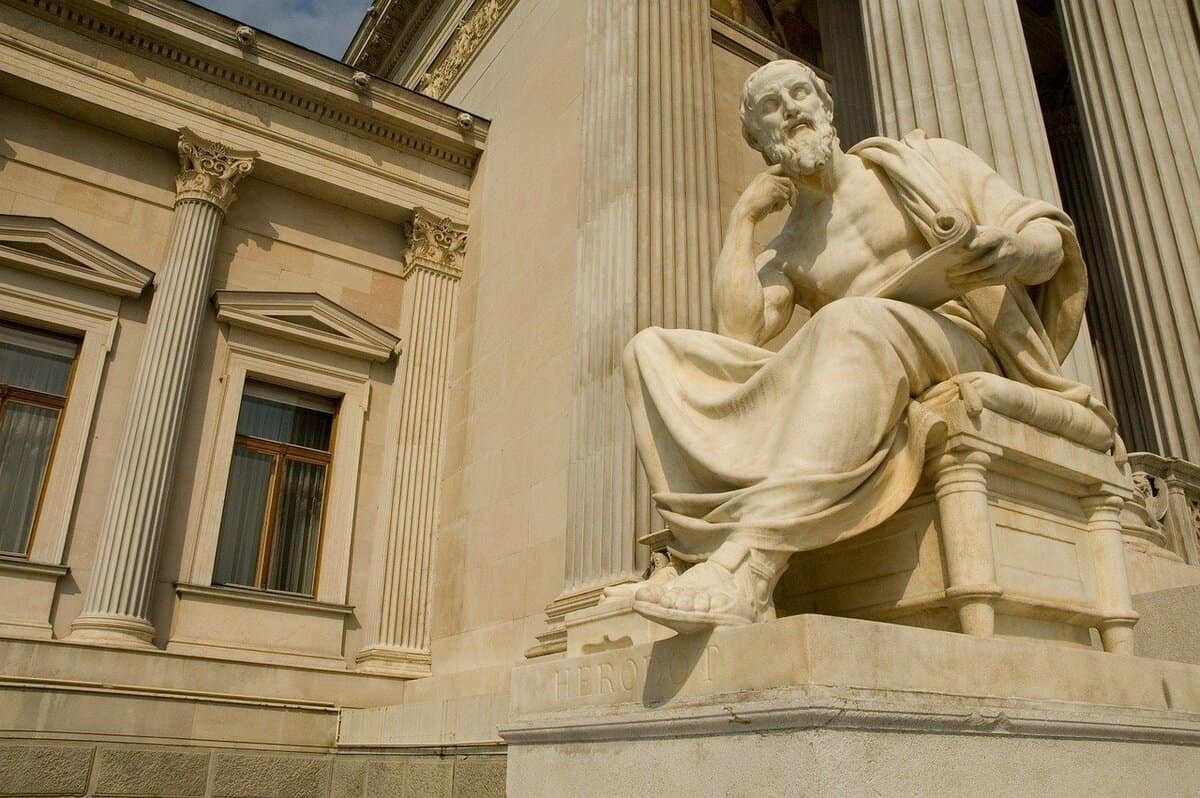

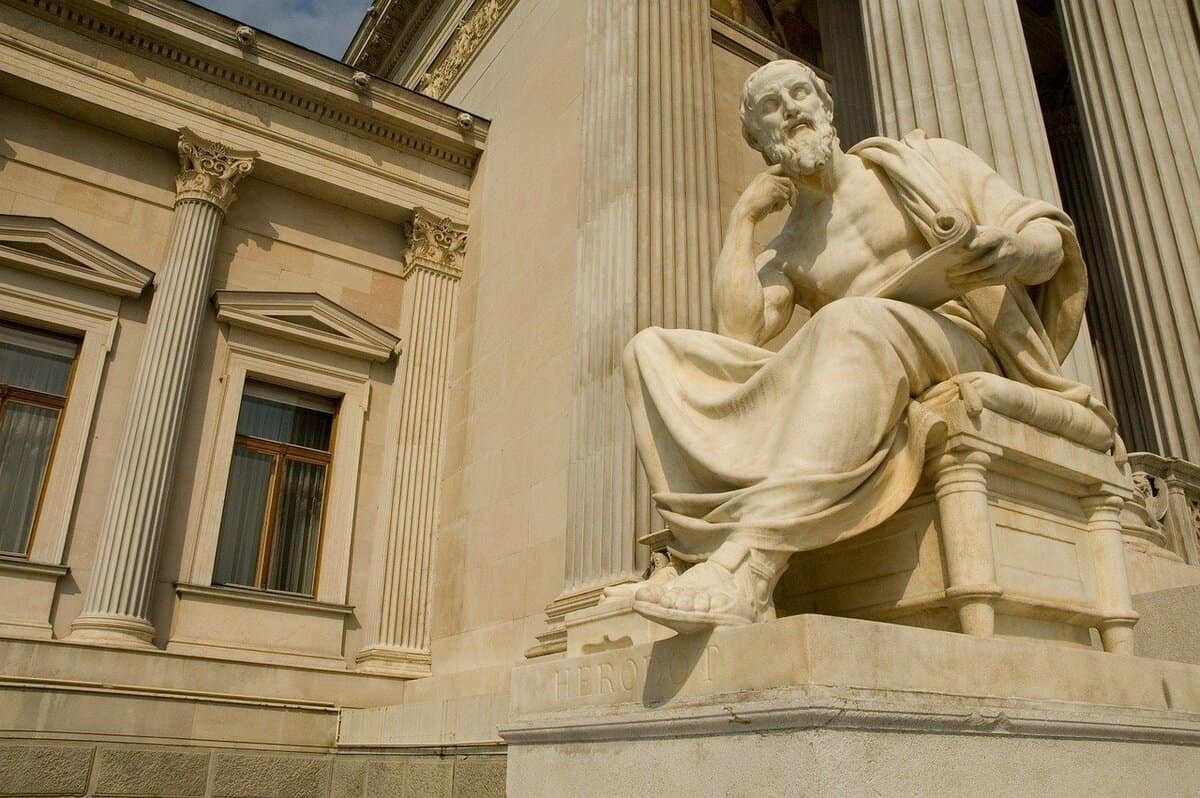

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

?Can you see how two very different philosophical traditions—one focused on lived meaning and the other on clarity and argument—might actually strengthen each other in contemporary thought?

You’ve probably felt the tug between big, human questions and the desire for crisp, defensible answers. In contemporary philosophy that tension often appears as a contrast between existentialism—concerned with authenticity, angst, and the situated human subject—and analytic philosophy—concerned with rigorous argumentation, linguistic clarity, and conceptual analysis. That split has shaped departments, journals, and public perceptions for most of the 20th century.

In this article you’ll get a clear, practical account of where these traditions come from, how they differ and overlap, and what a productive synthesis might look like today. You’ll see why bringing existential concerns into analytic frameworks (and vice versa) can sharpen debates in ethics, philosophy of mind, social theory, and cross-cultural philosophy.

You face philosophical problems in a world where technology, global exchange, and cultural pluralism complicate both meaning and method. Existential themes—alienation, freedom, the search for authenticity—are alive in public life, while the analytic toolkit offers ways to make those themes argumentatively precise. If you want philosophy to address practical problems (AI ethics, mental health, political legitimacy) you’ll benefit from techniques that combine both sensitivity to human experience and rigorous conceptual work.

Existentialism centers on the lived experience of the individual, freedom, responsibility, authenticity, and the conditions under which meaning is created or lost. Thinkers associated with the label include Søren Kierkegaard (often considered a proto-existentialist), Friedrich Nietzsche, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, and Martin Heidegger—though Heidegger’s relationship to the term is complex. Existentialism arose largely in reaction to systematic metaphysics and abstract moral theories, insisting that philosophers account for anxiety, mortality, and situated decision-making.

You should note that existentialism is less a single doctrine than a family of concerns and methods—phenomenological description, literary expression, and ethical reflection feature strongly.

Analytic philosophy values clarity, argumentative rigor, and attention to language. Origins are usually traced to figures such as Gottlob Frege, Bertrand Russell, G.E. Moore, and the early Ludwig Wittgenstein. Over the 20th century analytic philosophy diversified into formal logic, philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, epistemology, and metaphysics, often deploying technical tools to resolve conceptual puzzles.

For you, analytic philosophy offers tools to avoid ambiguities and to produce arguments that can be evaluated step by step. It tends to be suspicious of sweeping metaphysical claims unless they can be made precise.

You should be familiar with Kierkegaard’s emphasis on choice and faith, Nietzsche’s critique of values and the “death of God,” Sartre’s commitment to radical freedom and bad faith, Heidegger’s phenomenology of being, and Camus’ reflections on absurdity. These thinkers emphasize narrative, lived orientation, and the moral psychology of agency.

For analytic philosophy, look to Frege on sense and reference, Russell on descriptions, Moore on common sense, and the split early vs. later Wittgenstein—one concerned with logical form, the other with ordinary language and language games. In the mid-to-late 20th century, Quine, Carnap, Kripke, and Davidson expanded debates in logic, language, and metaphysics, often with formal techniques.

| Tradition | Representative Thinkers | Primary Emphases |

|---|---|---|

| Existentialism | Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Sartre, Heidegger, Camus, Beauvoir | Lived experience, authenticity, freedom, existential angst |

| Analytic | Frege, Russell, Moore, Wittgenstein (early/late), Quine, Kripke | Clarity, logic, language, argumentation, conceptual analysis |

This table gives you a snapshot so you can quickly place a thinker by orientation and emphasis.

Existentialism privileges first-person experience and insists that philosophical accounts must account for subjectivity. You’re asked to consider what it feels like to make decisions under uncertainty and mortality.

Analytic philosophy tends to emphasize intersubjective justification—you need arguments that others can assess, often rendered in third-person terms. The goal is not to dismiss subjectivity, but to translate it into propositions subject to evaluation.

While “continental” and “analytic” are broad labels, they capture stylistic differences. Existentialist writing often uses narrative, aphorism, and phenomenological description. Analytic writing prefers explicit argumentation, formal models, and conceptual clarification.

You should be wary of caricature: many analytic philosophers use literary examples, and some existentialists craft systematic claims. The styles nonetheless signal different priorities.

Existentialism tends to tackle broad, normative concerns (meaning, authenticity), sometimes at the cost of precision. Analytic philosophy delivers precision but can miss the existential texture of lived experience. Your task is to see how each can compensate for the other’s blind spots.

Linguistic analysis from the analytic tradition helps you clarify the content of existential claims—what does “authenticity” mean, what do you commit to when you say “I choose myself”? Conversely, phenomenological descriptions from existentialists can inform analyses of mental states, agency, and reference in philosophy of mind and language. For example, describing the felt sense of choice can help you specify the concept of intention for analytic purposes.

Existentialist ethics emphasizes responsibility and authenticity; analytic ethics offers tools for argumentation and normative theory. You can bring existential sensitivity to questions about moral motivation, while analytic frameworks can structure debates about obligation, rights, and justification.

Analytic work in philosophy of mind benefits from existential insights on selfhood—how you experience continuity, agency, and alienation. Phenomenological accounts can enrich analytic models of action explanation, while analytic clarity can prevent vague psychological claims.

You’ll notice overlaps between existential concerns and themes in Eastern thought. Buddhist reflections on suffering (dukkha), impermanence (anicca), and non-self (anatta) resonate with existentialist anxieties about contingency and mortality. Confucian emphasis on situated ethical practice echoes existential attention to concrete modes of living.

However, methodological styles differ. Classical Indian and Chinese philosophies frequently blend ethical practice, narrative, and soteriology in ways that align with existentialist attention to practice, while analytic tools are less present.

When you apply analytic tools to Eastern texts, you can clarify arguments about personhood, selflessness, and moral responsibility. Conversely, existential and Eastern concerns can challenge analytic assumptions about autonomy, individualism, and the structure of rational agency. That cross-cultural exchange can produce more robust accounts of the self and ethics.

You can use existential descriptions of bodily presence and intentionality to inform debates about consciousness and embodiment. Analytic work on functionalism, representational content, and mental causation benefits from phenomenological constraints—what an account of consciousness must capture to avoid missing the first-person perspective.

Example: Arguments about qualia or subjective experience often fall into either purely conceptual disputes or empirical corridors. Existential phenomenology reminds you that any object-level theory should account for the felt concerns that motivate action.

Existentialism’s focus on authenticity and responsibility has practical implications for politics—questions about collective identity, alienation under capitalism, and ethical resistance. Analytic methods help you assess arguments about justice, rights, and public reason. Where you combine them, you can produce policy-relevant arguments that are both humane and defensible.

Example: In debates about surveillance and autonomy, existentialist attention to alienation and loss of freedom can ground normative concerns; analytic reasoning helps formulate rights-based arguments and test policy proposals.

You’ll find value in bringing existential questions into tech ethics. As AI systems shape social recognition, work, and identity, concerns about authentic agency and alienation become urgent. Analytic philosophy offers ways to define responsibility, agency, and personhood for legal and technical frameworks; existentialism insists these definitions respect lived human concerns.

Practical outcome: When you design ethical guidelines for AI, combine precise definitions (who counts as an agent? what is autonomy?) with sensitivity to how systems shape life projects and meaning.

Existential therapy already occupies a space where philosophical reflection meets clinical practice. Analytic techniques (clear diagnostic criteria, testable interventions) complement existential approaches that prioritize personal narrative, meaning-making, and responsibility. You can thus develop therapies that are empirically informed and existentially respectful.

When you approach an existential theme—say, “inauthenticity”—first ask what you mean by the term in operational terms: behavioral markers, phenomenological features, or normative failures. That makes the claim accessible to analysis and debate.

Avoid reducing existential claims to purely behavioral descriptions. Preserve first-person reports and narratives as data that any satisfactory theory must explain.

When you assert that authenticity is valuable, use analytic tools to clarify the grounds for that value: instrumentally valuable, intrinsically valuable, or constitutive of agency. Then test the implications in policy or therapeutic contexts.

Let phenomenology inform conceptual definitions, and let analytic critique sharpen phenomenological accounts. You’ll often revise the initial descriptions as you discover counterexamples or boundary cases.

| Step | What you do | Why it helps |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Conceptual translation | Define existential terms in clear, testable language | Makes debates assessable |

| 2. Phenomenological grounding | Collect first-person reports and narratives | Ensures theory fits lived experience |

| 3. Analytic structuring | Formulate arguments, counterexamples, and models | Tests coherence and implications |

| 4. Application & feedback | Apply to ethics, AI, therapy, policy | Evaluate practical adequacy and revise |

This workflow helps you move from abstract tension to concrete synthesis.

You might worry that translating existential richness into analytic form flattens it. That risk is real: some existential claims rely on literary or rhetorical force. Your task is to retain expressive depth while making core claims accessible to scrutiny.

Academic sociology and hiring practices have historically siloed traditions. You may face disciplinary resistance, but the growing interdisciplinarity in philosophy and allied fields (cognitive science, comparative philosophy) creates openings.

When you compare Eastern thought with Western traditions, beware of imposing categories. Philosophical concepts must be interpreted on their own terms before being assimilated into broader frameworks.

You can enrich decision theory by adding existential conditions: decisions are not only utility calculations but involve projects, identity, and situated commitments. Analytic models of rational choice can incorporate project-relative utilities, which gives you better predictive and normative power.

Consider workplace alienation. Analytic surveys and data can measure job satisfaction, but existential accounts explain why certain roles undermine a sense of meaningful agency. Combining both yields design principles that are empirically effective and existentially respectful.

Analytic criteria for personhood (rationality, consciousness, agency) must be tested against phenomenological concerns (self-experience, intentionality). Recognizing both sets of requirements prevents hasty attributions of personhood to systems that mimic behavior but lack first-person depth.

If you’re teaching or designing a program, mix texts and methods. Pair existential works (Sartre, Heidegger, Kierkegaard) with analytic treatments in philosophy of mind, ethics, and language. Assign students projects that require both descriptive accounts of experience and formal argumentation.

For research, collaborate across specializations. A philosopher trained in analytic methods can partner with someone versed in phenomenology or comparative philosophy to produce richer papers and grant proposals.

You’ve seen that existentialism and analytic philosophy are not irreconcilable enemies but complementary approaches. Existentialism brings a necessary attention to meaning, mortality, and situated agency—matters that define why philosophy matters to human life. Analytic philosophy brings precision, argumentative discipline, and tools that make debates accountable. When you combine them thoughtfully, you can address contemporary problems—from AI ethics to mental health—with both rigor and humanity.

If you want to integrate these traditions in your own work, start small: clarify an existential claim, preserve lived reports, and then subject your claims to analytic scrutiny. That method will help you produce scholarship and practice that is intellectually robust and deeply relevant.

If you found this useful, consider sharing a specific problem you’re wrestling with—whether theoretical or practical—and you’ll get suggestions for concrete steps to apply this bridging approach.

Meta Fields

Meta Title: Existentialism and Analytic Thought: Bridging Traditions

Meta Description: Learn how existential concerns about meaning and freedom can be integrated with analytic clarity to inform ethics, mind, and practical philosophy.

Focus Keyword: Existentialism and Analytic Thought

Search Intent Type: Comparative