Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

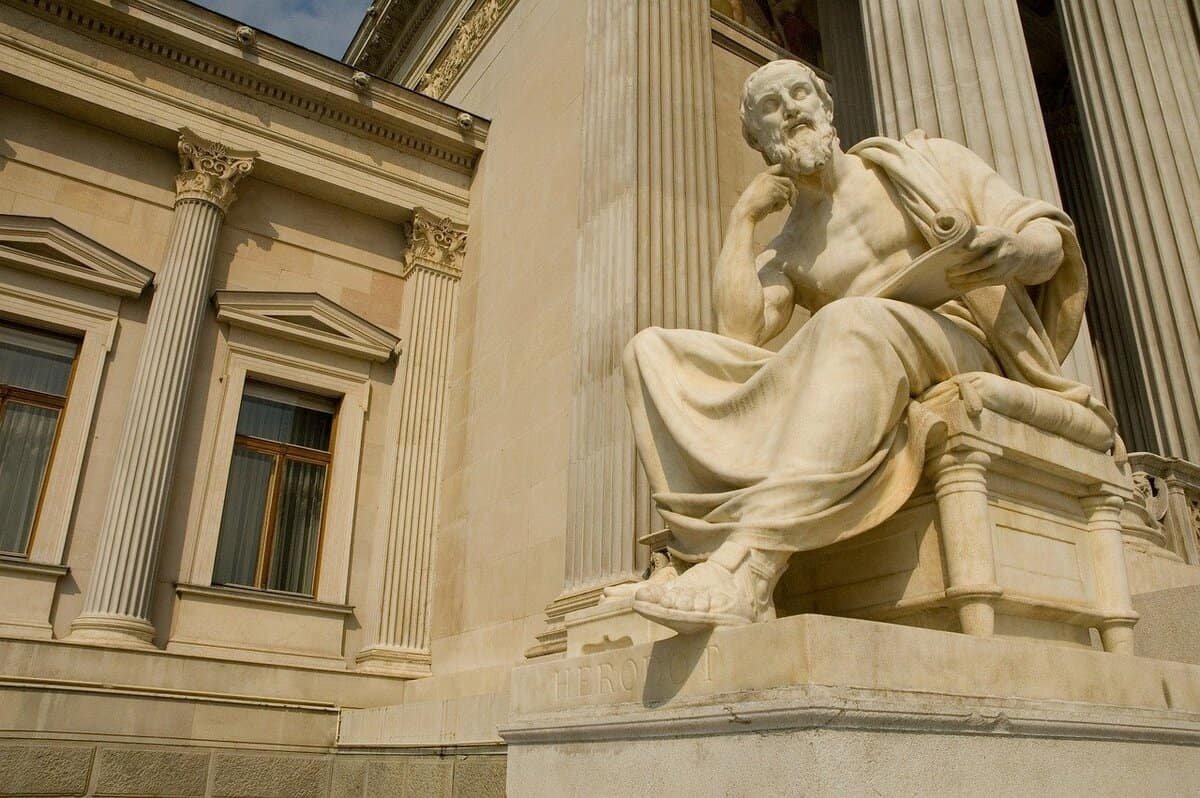

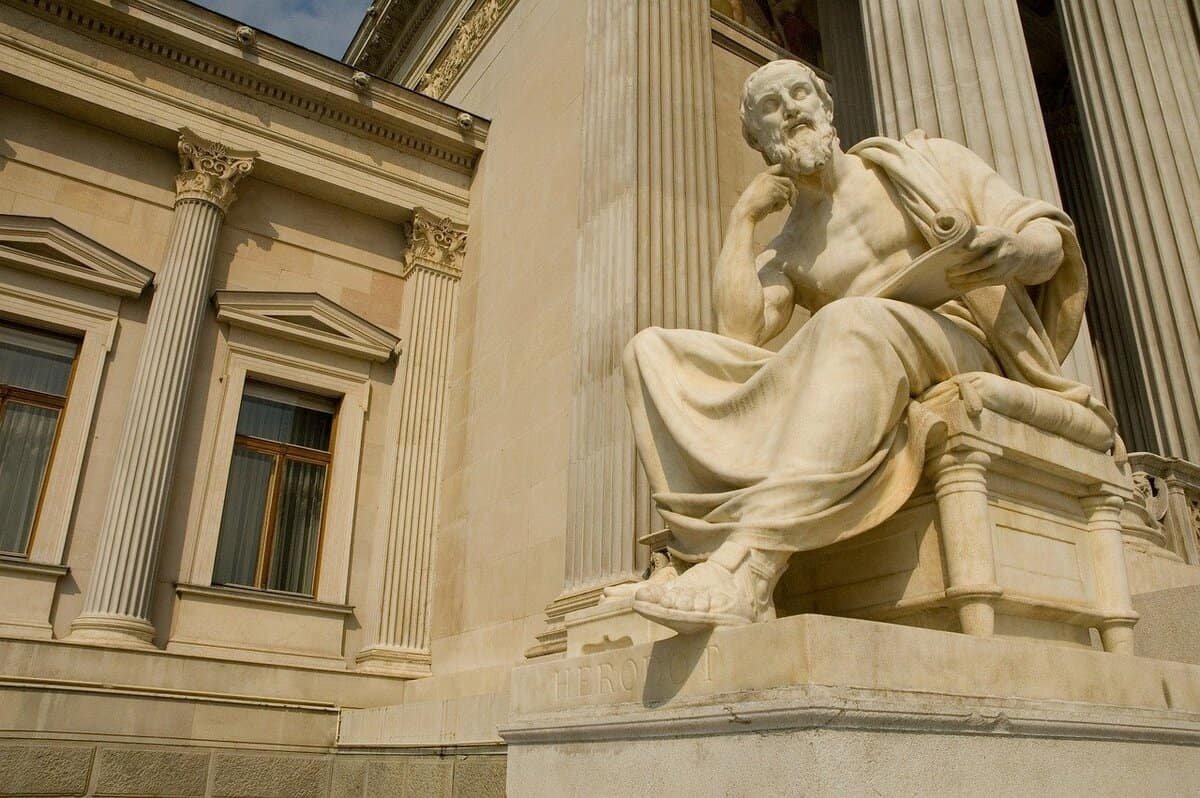

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

The Echo of Thought Across Ages

What if the ideas you take for granted about reason, rights, and governance were shaped by conversations that started more than two millennia ago?

You live inside intellectual frameworks that were forged, contested, and refined across centuries. From the assumption that reason can adjudicate truth to the language of rights and duties that governs modern institutions, many of the lenses you use to interpret the world trace back to Western philosophical traditions.

Consider that concepts like “human rights,” “scientific method,” and “individual autonomy” have textual lineages—Plato asking what justice is, Aristotle analyzing virtues, Aquinas synthesizing Christian theology with Aristotelian logic, and Kant recasting moral law as universal reason. In this article you will map those lineages, weigh their echoes in contemporary life, and see how comparative perspectives—especially from Eastern traditions—help you sharpen, challenge, and apply those legacies.

This piece aims to be a guide for professionals, thinkers, and curious readers who want to understand not just what Western philosophy taught, but how it continues to shape policy, technology, education, and personal practice today.

You should begin by getting clear on what counts as “Western philosophy.” At its core, Western philosophy historically emphasizes reasoned argument, clarification of concepts, and systematic theorizing about reality, knowledge, and value. Its roots are usually traced to ancient Greece, though interactions with Near Eastern and Mediterranean cultures matter too.

Western methods often prize analytical precision, dialectical argument (question and counter-question), and a drive toward universality—claims that purport to hold across contexts. That does not make the tradition monolithic: you’ll find diversity in approach, from Socratic questioning to medieval theology, from empiricist pragmatism to continental phenomenology.

You will make better sense of contemporary ideas by situating them in historical periods. Below is a concise breakdown of major phases and representative thinkers.

This period is where foundational methods of argument and inquiry are established. Socrates introduced critical questioning aimed at ethical clarity; Plato used dialogues to probe forms and the idea of justice (Republic); Aristotle systematized logic, metaphysics, and ethics (Nicomachean Ethics). These thinkers set enduring questions: What is knowledge? What is the good life? How should communities be ordered?

You’ll see thinkers like Augustine and Thomas Aquinas negotiating Greek reason with Abrahamic religious commitments. Aquinas’s Summa Theologica exemplifies the medieval project: using Aristotelian categories to articulate theology and natural law, producing a moral vocabulary that later shaped Western jurisprudence and ethical theory.

The early modern period reoriented authority toward reason and science. Rationalists (Descartes, Spinoza) and empiricists (Bacon, Locke, Hume) clashed over sources of knowledge. Political philosophy evolved with Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau theorizing social contracts that underpin modern liberal political institutions.

You’ll recognize major figures who challenged or refined previous ideas. Kant reframed ethics around autonomy and universality (Critique of Practical Reason). Hegel proposed dialectical development of history. Nietzsche critiqued moral foundations and announced the reevaluation of values. In the twentieth century, analytic philosophy emphasized language and logic, while continental thinkers (Heidegger, Foucault, Derrida) critiqued modernity, power, and subjectivity.

You should appreciate several core concepts that migrated from classical and modern philosophy into contemporary institutions and everyday discourse.

Reason occupies a privileged place in Western thought: from Aristotle’s syllogistic logic to Kant’s categorical imperative. You inherit a trust that rational inquiry can produce reliable knowledge and normative guidance, a trust that underpins legal reasoning, scientific methodology, and secular ethics.

The insistence on observation, experimentation, and induction—developed by figures like Francis Bacon and built into modern science—has made empirical validation a cornerstone of contemporary knowledge-making. You’re accustomed to evidence-based approaches because of this legacy.

Aquinas’s natural law tradition and later developments by Locke informed the language of rights: rights are often justified by appeals to human nature, reason, or social contract. This lineage informs constitutions, human rights frameworks, and legal doctrines in many countries.

Western philosophy’s focus on the individual as a moral and epistemic agent—accentuated by Enlightenment thinkers—reshaped political and ethical discourse. Concepts like personal freedom, responsibility, and self-determination draw on that heritage.

From Pyrrhonian skepticism to Hume’s empiricism, Western philosophy has fostered a critical stance that questions dogma. That skeptical impulse is vital in modern institutions that prize peer review, dissent, and pluralism.

You’ll see Western philosophical ideas reflected in concrete institutions and cultural habits. Here are key domains where the legacy is unmistakable.

The modern nation-state, constitutional liberalism, separation of powers, and democratic representation have philosophical antecedents. Hobbes justified centralized sovereignty for order; Locke defended property and consent; Montesquieu argued for institutional checks. These ideas translated into constitutions, judicial review, and civic norms.

The scientific method and the idea that rational inquiry yields progress underlie modern universities, professional standards, and evidence-based policy. You benefit from, and take for granted, systems that prize testing, peer critique, and disciplinary specialization.

Legal concepts of due process, equality before the law, and universal human rights bear traces of natural law, Enlightenment ethics, and debates about personhood. International human rights language often invokes universal claims grounded in reason and dignity.

Philosophical ideas about individual rationality and property shaped economic liberalism. Adam Smith’s moral sentiments and later economists’ models presuppose agents making choices within institutional frameworks. You encounter these assumptions in corporate governance, market regulation, and managerial ethics.

If you want a clearer sense of what’s distinctive about the Western legacy, comparing it with Eastern thought helps. Avoid caricatures: both traditions are internally diverse. Yet comparative differences point to useful contrasts for reflection.

| Aspect | Typical Western Emphasis | Typical Eastern Emphasis |

|---|---|---|

| Epistemic method | Analytic argument, abstraction, universal claims | Holistic insight, contextual wisdom, praxis |

| Moral perspective | Individual moral autonomy, universal principles | Relational duties, role ethics, harmony |

| Metaphysics | Substance/essence, causality, identity | Process, interdependence, non-duality (in some schools) |

| Political vision | Rights-based frameworks, rule of law | Communal harmony, role of ritual and hierarchy |

| Goal of philosophy | Truth, systematization, critique | Right conduct, self-cultivation, balance |

You can use this table not to pit traditions, but to see how each offers corrective strengths. For instance, Western focus on universality helps build rights-protecting institutions, while many Eastern practices emphasize social harmony and embodied practice that can temper individualism.

You should recognize that Western philosophy is self-critical. Internal critiques have reshaped its trajectory and made it resilient.

Feminist philosophers have interrogated assumptions about autonomy, reason, and the public/private split, pressing for recognition of gendered power structures. Postcolonial critique exposes how philosophical universalism sometimes masked imperial and exclusionary practices, urging historical reckoning and pluralist reorientation.

Thinkers like Nietzsche, Foucault, and Derrida challenged the idea that reason operates outside power or history. You now encounter the notion that knowledge is embedded in institutions and discourses, which invites you to question taken-for-granted categories.

American pragmatists (Peirce, James, Dewey) reframed truth as something that works in practice and emphasized consequences over abstract absolutes. That practical orientation has influenced education, policy analysis, and contemporary applied ethics.

You can trace many modern practices back to philosophical roots and find practical guidance for contemporary dilemmas.

Kantian respect for persons, utilitarian calculations, and virtue ethics all compete and complement each other in hospital ethics committees. You see this when doctors weigh patient autonomy, beneficence, and justice.

When you consider algorithmic fairness, transparency, and accountability, you’re dealing with philosophical descendants of epistemology and moral theory. Questions about what counts as “knowledge” and whose interests algorithms serve are fundamentally philosophical.

Philosophical debates over punishment, forgiveness, and reparation shape legal frameworks for transitional justice and human rights policy. You may work within institutions that deploy these concepts in policy design.

Stoicism’s emphasis on resilience and modern virtue ethics influence leadership training. You can apply ethical frameworks—deontological constraints, consequentialist assessments, and character-based thinking—to corporate governance, compliance, and stakeholder strategy.

Rawlsian ideas about justice as fairness and Habermasian models of communicative action inform contemporary approaches to policy deliberation and participatory governance. You will find these principles in attempts to design inclusive deliberative forums and fairness-minded algorithms.

You don’t need a degree in philosophy to apply these ideas. Here are practical steps to translate philosophical heritage into everyday professional tools.

When you evaluate reports, policies, or technical proposals, map premises and conclusions. Learn the basic fallacies and test whether conclusions follow from premises. This habit will improve decision quality and communication.

When facing a dilemma, apply multiple ethical lenses: ask what rules apply (deontology), what consequences will follow (consequentialism), and what virtues or character traits the action cultivates. The interplay will give you richer, more defensible decisions.

Understand the intellectual genealogy of policy concepts—what does “rights” mean in your context? Which assumptions about the individual or society are embedded in your models? Historical literacy prevents category mistakes and unexamined importation of assumptions.

You should not treat traditions as mutually exclusive. For instance, adopt Western analytic tools for clarity while learning embodied practices (like mindfulness or relational ethics) from Eastern traditions to balance individualism with communal well-being.

Create spaces for dissent and systematic critique—peer review, ethics boards, problem-framing sessions. Western philosophy’s critical apparatus can be institutionalized to reduce groupthink and bias.

Below is a timeline table to help you visualize major thinkers and their primary contributions.

| Era | Thinker | Key Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| Ancient | Socrates, Plato, Aristotle | Dialectic questioning; theory of forms; virtue ethics and logic |

| Medieval | Augustine, Thomas Aquinas | Theological synthesis; natural law; moral theology |

| Early Modern | Descartes, Locke, Hume, Hobbes | Rationalism vs empiricism; social contract; skepticism |

| Enlightenment | Kant, Rousseau, Montesquieu | Moral autonomy; justice as fairness seeds; separation of powers |

| 19th Century | Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche | Historicism; critique of capitalism; critique of morality |

| 20th Century | Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Foucault, Rawls | Language games; existential ontology; power/knowledge; political liberalism |

| Contemporary | Analytic and Continental currents | Applied ethics, philosophy of mind, AI ethics, global justice |

This table gives you a compact reference to trace where major modern ideas originate.

You should be aware of pitfalls when reading “Western philosophy” as a single monolith.

Recognizing these nuances makes you a more sophisticated reader and practitioner.

You live in a world shaped not just by technology and markets, but by centuries of argument about reason, justice, and the good life. Western philosophy’s legacy is everywhere: in the courtroom, the lab, the boardroom, and the way you reason through dilemmas. That legacy is powerful because it offers methods—critical analysis, systematic theorizing, and a language for rights and duties—that you can deploy in practical contexts.

At the same time, you will benefit from comparative humility: Western approaches have strengths and blind spots. Bringing comparative perspectives, critical scholarship, and pluralist practices into conversation improves outcomes—ethically, institutionally, and personally.

What practical step will you take next? Perhaps you’ll map an argument in a policy paper, apply multiple ethical lenses to a business decision, or read a classic with an eye to contemporary application. Leave a comment, try one exercise, or read a primary text (Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, Kant’s Groundwork, or Confucius’s Analects) and reflect on what it changes in your practice.

Meta Fields

Meta Title: Western Philosophy’s Enduring Legacy — Modern Thought

Meta Description: Learn how Western philosophy shapes modern institutions, ethics, science, and policy; practical insights for professionals seeking intellectual tools.

Focus Keyword: Western philosophy legacy

Search Intent Type: Informational / Comparative / Analytical / Practical